A Conversation on Desert Pupfish and the Salton Sea

March 15, 2021

|

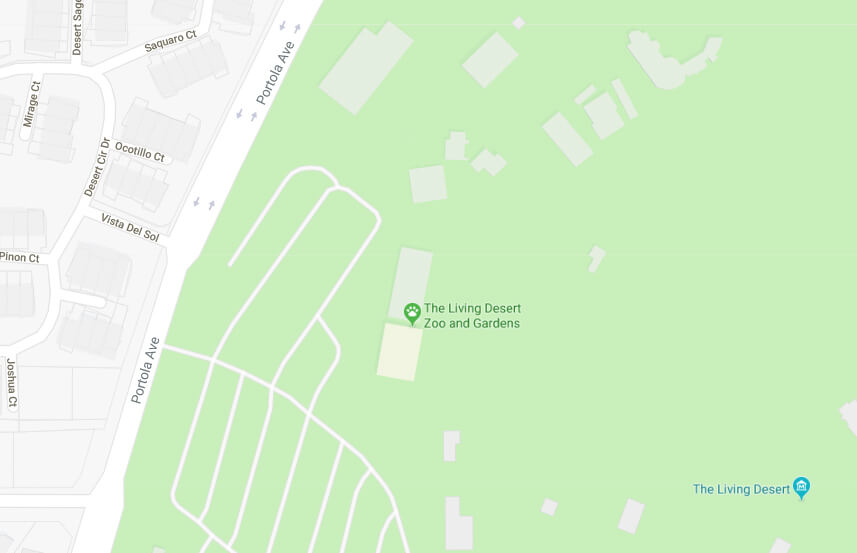

As a conservation biologist, Kyle Mulroe uses tools of biology and engineering for the conservation of wildlife at The Living Desert since 2019. Natalie Gonzalez, Assistant Conservation Scientist, joined The Living Desert in 2020 with a degree in Ecology, Behavior, and Evolution from UC San Diego. |

The Living Desert partners with outside organizations for a majority of our conservation work. We would like to thank Coachella Valley Mountain Conservancy, Bureau of Land Management, and California Department of Fish and Wildlife for their funding and cooperation of our desert pupfish conservation. The Living Desert works with these partners to restore the Salt Creek watershed (near the Salton Sea) for the conservation of the desert pupfish.

Kyle: Natalie, growing up in the Southern California desert, tell me about your perception of the Salton Sea. How has that changed since you started working at The Living Desert?

Natalie: Growing up just south of the Salton Sea, I often heard stories of the enjoyment the Sea once brought to local communities but how the Sea had quickly become labeled as toxic due to exposed playa and mass fish die-offs. It was not until high school that I learned this is still a place of wonder for wildlife and a valuable ecosystem. Protecting the sea and as a consequence the species which rely on it as well as the neighboring human communities has come to feel like a race against time. Working on habitat restoration near the Salton Sea with The Living Desert has allowed me to take part in the conservation of surrounding ecosystems.

Natalie: Had you heard of the Salton Sea before moving to the Coachella Valley?

Kyle: I had heard that the Salton Sea is California’s largest lake, with over 300 square miles of surface area. But until I moved here from the San Francisco Bay Area, that was all I knew. I started seeing pictures of this hypersaline environment and relics of old docks and boating areas. While the sea is in great peril, some of the surrounding ecosystems are still quite alive. During a recent fieldwork expedition, I went along the controlled marshes on the southeastern edge and saw majestic great blue herons, sleek white egrets and flocks of swimming water birds. It is a birder's paradise.

Natalie: Why is the desert pupfish the only native fish species to our desert? Why is it found in Salt Creek, a tributary of the Salton Sea?

Kyle: Western pupfishes have been evolving in California watersheds for over six million years! The desert pupfish (Cyprinodon macularius) diverged from other pupfish species around 600,000 years ago in the Lower Colorado River Basin. Over the course of time, desert pupfish individuals and populations survived in conditions that no other fish did. Desert pupfish withstood the great swings in temperature, salinity and dissolved oxygen that can be found in desert aquatic ecosystems. Desert pupfish have likely utilized Salt Creek for millenia, and are well adapted to the wide range of water temperatures and changes in salinity found at the delta with the Salton Sea.

Natalie: Being new to the desert, equipped with a degree in marine biology, what were your thoughts when first introduced to the desert pupfish?

Kyle: As an amateur aquarist growing up, I had learned of the Devil’s Hole pupfish in Death Valley. They were considered “the rarest fish in the world,” according to their Wikipedia page. Their unique adaptations to a hostile environment piqued my interest and imagination. While the fish tanks I kept were saltwater reef tanks, my hobbyist friends and I loved learning about fish and aquatic ecosystems of all kinds. The unique ecology surrounding the Devil’s Hole pupfish was again mentioned in my studies at UC Santa Cruz. Only after moving to the desert did I learn of the desert pupfish specifically and see this rare fish with my own eyes.

Kyle: You have worked on plant propagation for a few different projects, and now Salt Creek. What are some of the strange, weird, magical ways that you’ve learned to propagate to seeds here at The Living Desert?

Natalie: Some seeds require very specific signals or processes to germinate. For the species we are propagating from Salt Creek, some will germinate after a 24-hour soak in water, but one species would not germinate, even in a greenhouse, until spring approached and the total amount of daylight had increased. Bob Linstead, former Botanical Propagator here at The Living Desert, introduced me to some of the more unique methods of mimicking natural processes that induce germination. One instance comes to mind: Bob was working with seeds that germinate after passing through an animal, so he held the seeds in his mouth for an entire day. I am not sure if it worked but it was definitely creative problem solving!

Kyle: How were plant species propagated for this restoration selected?

Natalie: During our initial site visit to Salt Creek, we identified 34 different native species occurring in the area. Of the species we identified as native and already existing in the area, we identified which species are riparian, could grow near the streambed, and which species had high salinity tolerances. Sea-blite (Suaeda sp.), iodine bush (Allenrolfea occidentalis), Salt bushes (Atriplex canescens and Atriplex polycarpa) and goldenbush (Isocoma sp.) can be found growing in the Desert Plant Conservation Center on grounds at The Living Desert.

Did You Know...

- The Living Desert has been conserving desert pupfish for almost 50 years! The desert pupfish was the second animal species conserved here starting in 1972. The first was a kit fox!

- There is a beetle capable of defoliating and taking down large stands of tamarisk! The tamarisk beetle (Diorhabda carinulata) and its larvae feed on the leaves of tamarisk, weakening and often killing the plant. This relationship has made biological control of tamarisk an effective strategy although the species is regulated by the USDA and cannot be translocated to new sites.

- The Salton Sea is not just an “engineering accident” from one faulty canal. The Salton Sea has naturally filled and dried repeatedly over millennia as the Colorado River watershed has changed its course. Years of great floods have changed the river’s speed, volume and course, spilling into the Salton Sink and forming temporary seas.

- The desert pupfish is found naturally in only two natural tributaries which feed into the Salton Sea: San Felipe Creek on the southwest side of the sea and Salt Creek on the northeast side.

To learn more about this project check out our blog page at livingdesert.org/blog/