My Dinner With The Chief

February 16, 2018

A day ago, I had one of the highlights of my professional career, something that I have long read about in African adventure books: I had dinner and a game drive with an African Chief and his Royal Family. And, more importantly, it was a transformative experience in what has been a massively transformative work trip to South Africa.

Meeting the Chief and the many similar experiences, do not come about commonly and certainly not easily. I feel this came about because of our success in two core hallmarks of successful community based conservation: cultural respect and collaboration. For too long, conservation and community work in Africa has been done in a very western fashion. What works efficiently in business meetings in the West, where we speak directly and efficiently about the goal at hand, is often seen as rude and insensitive. I work hard to be as respectful of the local culture as possible, as a tall, white, Western man. However, how we look unfortunately determines how others interact with us, and I am often held accountable for the follies and misdeeds of my predecessors.

Therefore, before starting any of our community-based work, we needed to respectfully and gingerly secure permissions from the Chiefs of the two main areas in which we worked. Once this was accomplished, we needed to clear our work with the relevant Ndunas who act as the local administrators in the hereditary Chief’s Kingdom. Only then, could we actually head into the communities and ask if people would be willing to share their insight and knowledge with us.

In many traditional African communities, these permissions are not given to outsiders. For a few months before we arrived here in South Africa, I was terrified that we would not be allowed to talk with people in the local communities to assess the social impact of the Black Mambas Anti-Poaching Unit on their neighbors in their home communities. Not receiving the permissions would have scuttled our work, and fear of it gave me many restless nights of worry.

Thankfully, I had put my fate in the skilled hands of the Mambas. Lewyn, Marble, and I worked to create and implement our plans for how to respectfully introduce our team to the two Chiefs in whose Kingdoms we hoped to work. Addressing the Chief is not done as though she or he is just another person. You must come bearing gifts, be deferent, and wear the appropriate, formal, and gender-defined clothing. If you do not secure permission, you are not allowed to work in their kingdoms.

Amazingly, the super-talented and youthful Lewyn was able to secure permission from the woman Chief who led the Maseke people, on her own and suddenly! On a regular basis over the last month, Lewyn made the seemingly impossible happen, and this was only the greatest of that streak.

However, the Hluvukani Chief Mnisi was another story. We had heard that he was a notoriously difficult leader with whom to garner an audience, and his kingdom included three of the four communities with whom we needed to speak. We had instead prepared to speak with his lead administrator and a pair of Ndunas who granted us the preliminary approval for our work, pending approval by the Chief and the rest of his Nduna Council. What we were unprepared for was the sudden invitation to speak with Chief Mnisi ourselves, just as we were getting ready to depart.

We went into Chief Mnisi’s office and he was quite surprised to hear that 26 of the 36 Mambas (72%) were from his kingdom. He asked us to explain our project and the goals for it and then gave us permission to work in his kingdom. He then asked many questions about the Mambas and what they did. Then, he expressed interest in meeting the Black Mambas as a team. Coincidentally, the Black Mambas Anti-Poaching Unit was to have a rare skills demonstration as a team in a few weeks. We invited him to come, and he immediately accepted. Understandably, this was both exciting and terrifying. It is not every day that you have Royalty visiting!

We received the subsequent permissions from the Ndunas in the four communities we worked (each of these experiences were separate stories in their own rights), and quickly completed all of our 120 individual interviews over the next two weeks. See my last blog for more about that process.

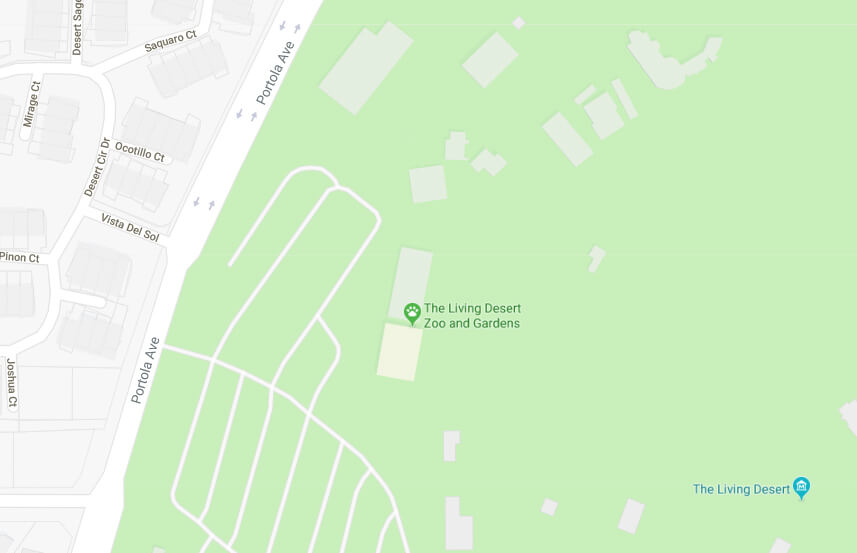

On the day of the Mamba skills demonstration and individual recognition event, typically called a Mamba Parade here, they were to drill and share their experiences with the audience. We hoped that the many days of preparation by the Mambas, and of our efforts in reaching out to Chief Mnisi would ensure that he would attend. Visits by chiefs rarely happen to relatively far locations, such as where the Mamba Parade was to occur.

Fortunately, he and the Royal Family showed up. Craig Spencer, the Director of the Mamba Program, gave an excellent introduction on the Mambas and extolled their many accomplishments. The Mambas were brilliant in demonstrating their many regimental skills. The Royal Family were clearly impressed with the entire exercise and asked many questions about the Black Mambas Anti-Poaching Unit.

I was lucky enough to be requested to attend dinner with the Royal Family immediately afterwards, along with Lewyn and Marble. We then were to go on a game drive across the land that the Mambas so diligently patrol. As the only outsider, I felt quite honored to get to speak with Chief Mnisi and his family for so long. Together, we saw only the second black rhino that I was to see on my entire trip to Africa, and spend more time watching him than I had ever been able to see before. We slowly and carefully approached the rhino and he did not flee, but instead watched us curiously until he accepted our presence and allowed us to go about our business.

In all situations, it seems, that if we respect the proper protocols and cultural mores, we can have amazing experiences where good things result. I am a person who has loved animals his whole life and have prioritized animal encounters over anything else. However, getting to meet and interact with so many kind and welcoming people from the Tribal Communities here in South Africa has convinced me that what we are doing is right, and how we are doing it is crucial.

We can make an even greater difference for helping to conserve nature by also working to secure and conserve the cultures and well being of the people living nearby. Respecting local culture is central to all of what I do, and I hope that you will agree with its importance.

As I write this on the plane home, I am hugely grateful to our core research team of Liz, Chantal, and Romy for all their hard and patient work that has more than achieved all we hoped to accomplish. These women are rock stars of social science! Similarly, thanks to Lewyn, Marble, Felicia, Collet, and Precious – the Mambas who rose to the great challenge of our community surveys – and to Craig, Lisa, Warren, Leonie, and Pieter of Transfrontier Africa who made living and transportation possible. Thank you, yet again, to the kind community members in Maseke, Welverdiend, Hluvukani, and Acornhoek who agreed to share their thoughts and ideas – and of course to Chief Mnisi of the Hluvukani and to the Chief of the Maseke.

Last, I wanted to thank the wonderful Black Mambas Anti-Poaching Unit for providing us all inspiration and hope for the future of conservation. You are the change that I want to see in the world.

Thanks for reading about our work trip over these last five lengthy blog entries. It has been really helpful to organize and then share my thoughts with you!