Conservation in a Privately Held Landscape

June 7, 2018

With only a few exceptions, most conservation activities focused on protecting ecosystems (as opposed to species) that happen in India happen with the government declaring protected areas and removing the people from the land. This approach is modeled on how National Parks are created in Western countries, an idea that began when the Republican President Ulysses S. Grant signed the legislation creating Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming in 1872.

A notable and frequent consequence of the national government intervening in creating parks is that it displaces people from land that their family and ancestors may have lived on and worked for generations. The Indian government usually, but not always, provides compensation to the displaced people in the form of housing and sometimes employment – a process that is dubiously called “rehabilitation” here. By forcibly removing people in this manner, governments often create what are essentially conservation refugees who are rarely advocates for conservation and more likely to be enemies of the process.

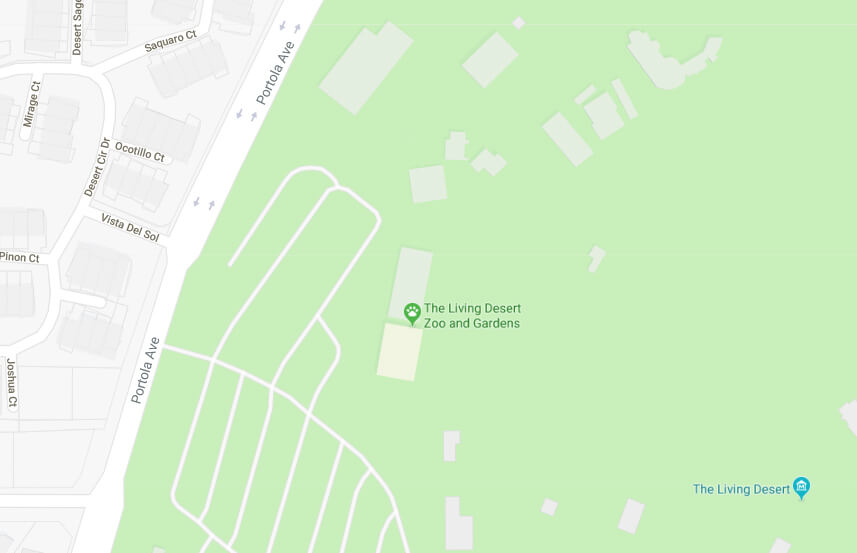

One of the exceptions to this Indian national tendency is in the Northern Western Ghats, where the Applied Environmental Research Foundation works. In the Sangameshwar Block (akin to a municipality) where they focus their efforts, all the nearby land where they work is privately owned. As a Fulbright Specialist, I have been in this landscape for the last three and a half weeks now and have been able to see most of the tools and approaches that they use.

By working with both individual and community landowners over the last two and a half decades, AERF has created a diverse portfolio of financial, spiritual, and cultural benefits that can be derived from intact forests. Instead of refugees, AERF is working to create conservation advocates. The communities in which they work often seek out AERF and request to participate.

As with any good investment portfolio, the conservation tools range from family-level efforts to reduce wood consumption for cooking (the MyForest bio-stove that I spoke about in Blog #5), to community-level reforestation of the Sacred Groves surrounding the community temple (more in a future blog), to creating and connecting Fairwild-certified fair trade fruit and seed products that only come from healthy forests, to Community Forest Agreements where they agree to not cut big trees or otherwise harvest non-timber forest products (NTFPs) unsustainably for a 10 year period of time in exchange for a regular financial subsidy.

All together, these and the other creative approaches that AERF has developed have enabled them to work with communities to protect over 5,000 acres of mature forests in a landscape where there would otherwise be next to none. That is a conservation success story.

As AERF demonstrates so well, protecting landscapes can be done in a way that protects the natural world, ensures the well-being of the communities dependent upon it, and ensures that the local economy (and culture) is nurtured. This “triple-bottom line” (natural, human well-being, and economic) can be best done through community-based conservation.

Not only does community-based conservation not create conservation refugees, this approach creates conservation advocates! Helping to develop the natural and social scientific skills and capacity that are necessary to ensure these successes is why I am fortunate enough to be here in this wonderful country, working with these amazing people.

Isn’t life amazing?

Disclaimer: This blog hosted by The Living Desert Zoo and Gardens is not an official U.S. Department of State site. The views expressed on this site are entirely those of its author and do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of State or any of its partner organizations.